The Covid-19 pandemic has had severe consequences for women. They weren’t just overrepresented among the frontline workers who risked their lives to provide health care, child care, and other essential services. They were also at a higher risk of losing their jobs as retail stores, restaurants, and other service-sector businesses laid off workers or closed entirely.

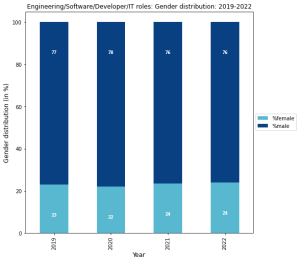

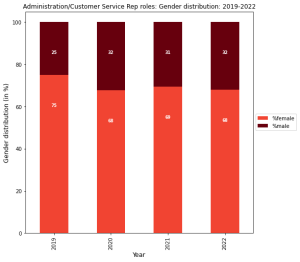

Even prior to the pandemic, women were more likely to work in part-time, low-paid, or tipping occupations — meaning they were struggling to make ends meet even before 2020. Recent research from Eightfold shows that even in 2022, females occupied only 24% of the highest-paying tech roles in the U.S., compared to holding 68% of administrative or customer service positions.

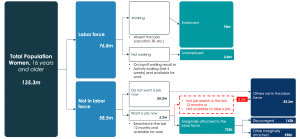

Today, there are roughly 2.8 million unemployed women (defined as over the age of 16 and actively seeking employment during the past four weeks).

But beyond this “official” number lurks a truer and grimmer figure.

What Fails to Show Up in the Data

Solely looking at the above unemployed number doesn’t reflect women (ages 16+) who are not in the labor force. There are currently 58.5 million such women who may or may not want a job.

A subset of that group, 3.2 million, are those who do want a job, searched for a job in the last year (but notably not the last month), and are available for work. But the real eye-opener here is that out of those 3.2 million, 2.5 million have stopped their job search and left the labor force altogether.

Unfortunately, the number of women not in the labor force has been persistently high throughout the pandemic and has yet to come back to pre-pandemic levels.

Economists had wrongly assumed that once vaccines were available, these women would go back to work. But the rates of women in the labor force did not significantly increase during the second and third quarters of 2021, roughly the time of the vaccine rollout.

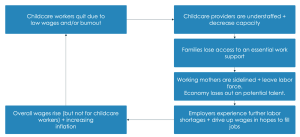

A subsequent assumption was that once care centers and schools reopened in the fall of 2021, we would see women come back into the workforce. And while there was some uptick in participation, the magnitude was not as great as expected. A likely reason could be the massive childcare shortage for children too young for school, as well as the closures of after-school programs.

Sure enough, an Indeed survey showed that among women who were unemployed but not urgently looking for work, nearly one-fifth said care responsibilities were the reason.

Coupled with low wages for childcare workers, this has created a cycle of unemployment:

What Now?

Improved childcare-support policies from the government would help pull more women into the labor market. Other countries that offer such support have substantially higher labor force participation for women. In the meantime, employers can take certain actions, including:

1. Providing flexibility to employees. Companies can offer flex time, which, contrary to some critics’ views, doesn’t mean people will work less, be less productive, or be less innovative.

2. Offering childcare subsidies and/or developing partnerships with childcare providers. A great resource (one of many) is the Care Economy Business Council, which shares innovative approaches and advocates for long-term solutions to childcare issues.

3. Reskilling those with a GED or high school diploma to become childcare workers. Cities like Milwaukee have found an interesting solution to find childhood educators — an adjacent role. Milwaukee has created a dual enrollment program for high-school students, creating a pipeline of early childhood educators from the local community to solve the shortage of workers.

4. Reducing bias by hiring for potential. Focusing on skills and potential — rather than other criteria irrelevant to a role — to find the best candidates would not only support diversity hiring goals but will help ensure that women are given a fair shot at jobs.

5. Eliminating gender pay gaps. Employers should be fair with their compensation to prevent the downward pressure on women’s future earnings. Every 10% increase in women working is associated with a 5% increase in wages for all workers.