Listening isn’t a natural response. It’s particularly unnatural for the people you need to have listen most — hiring authorities.

You might think they’d be intensely motivated to hear about your headhunting ability to:

1. Fill crucial openings with

2. Qualified candidates with

3. No obligation to hire, and

4. At no cost unless they do.

You might also think they’d be ecstatic your guarantee gives them a free replacement — even a refund.

But you’d be wrong. Serious hirers are numb. They’re deaf and dumb. Lost in the jungle, they run around aimlessly trying to get the same job done with fewer people. They’re so pressured justifying what they’re doing to fill the opening, explaining why the work isn’t getting done, and trying to keep overworked employees from quitting, that your call is often an unwelcome interruption. Almost any call is.

Over the past 47 years, I’ve heard (and used) enough recruiting “openers” to fill a jungle jokebook. Nobody knows whether they worked because some recruiter was lucky — or whether they worked at all.

This is no ordinary prospect we’re dealing with — he’s one that needs to be trained to listen — forced in fact. He needs to be turned from a hirer into a “telehirer.”

There are two tough training tactics to use. Here they are:

Tactic #1: Appeal to the Hirer’s Real Self-Interest

Almost every canned opener I’ve seen (and used) assumes the victim wants to hire someone fast, cheap and sure. That’s why the adjectives used are variations of “immediate,” “no obligation,” and “qualified.”

Canned openers fail because they’re not sharp enough to penetrate the hirer’s mind and spear his heart.

In Seeds of Greatness, psychologist Denis Waitley suggested, “In communicating with others, always treat behavior and performance as being distinctly separate from the personhood or character of the individual you are trying to influence.”

You’d think the supervisor would realize how properly filling the job will help him succeed. But few do because hiring is an abstraction until candidates are presented. Then it’s a distraction. Even the most proficient hirers know it’s a time-consuming, frustrating ordeal.

Use This Checklist

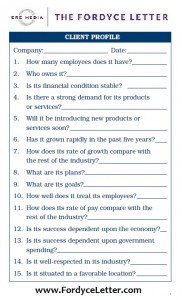

Then how do you get his attention? By having the answers to questions like the ones on this checklist. (Click the image to download it. Print it out and use it as is, or use it as a template and create your own.)

We’ll gladly complete this checklist for you on any supervisor. We’ll only charge you for a half-hour of time, too; 15 minutes for the time it took to convince you it can be done, and 15 minutes for doing it.

You just call into the company, find someone familiar with the supervisor, and say:

“I’ll be helping (name of supervisor) look for qualified people to join (name of employer). He’s not in right now, and I’d appreciate it if you could answer a few questions.”

If someone declines, call someone else. Then whip out that profile and start asking.

In How to Turn an Interview into a Job, I wrote:

Plan on doing a lot of listening. You will find that a lot of listening is exactly what you will be doing! People love to talk about their jobs and their companies, and at some point along the line you probably will be the one to terminate the conversation.

And here’s the bonus: If you play your cards right you may actually end up with an internal referral. There is no more potent entry into any company, since the interviewer will feel obligated to act upon the referral and go forward with an interview. If you look at all good, he’ll be inclined to give you the benefit of the doubt. Otherwise he’ll be faced with more than one embarrassing elevator ride if he rejected you for the position.

As a recruiter, the same rule applies to you. How could even the most job secure, hostile supervisor avoid a direct statement like:

“Hi. This is Marty Shaw. Nancy Farber mentioned that you were looking for a design engineer. I understand that you’re in line for a promotion. Since I’m a recruiter specializing in designers, we should know each other. In fact, we’re neighbors!”

You won’t find words like that in canned openers. The approach goes beyond them to deal with a hirer where he works and lives.

Specifically, it:

1. Forces the hirer to listen. (He wouldn’t dare hang up on Nancy Farber’s friend.)

2. Impresses him with your knowledge. (His promotion potential.)

3. Interests him. (You may know more about the promotion than he does.)

4. Credibly describes how you can help. (You’re a specialist in recruiting the person he needs.)

5. Suggests a mutual benefit. (Becoming better acquainted.)

6. Aligns with him. (You’re neighbors.)

That’s just the beginning. Just think how much better you are at sending the “right” candidates when you’ve scoped out the interviewer!

Use that Hiring Authority Profile. Each one is completed differently. Each hirer is different. Each need is different. Knowing that need is the key to teletraining a telehirer.

As you complete profiles, you’ll find three areas of self-interest that surface constantly:

1. Keeping his / her job.

The hirer is usually on a tightrope, because the opening itself threatens his job security.

Why did the ex-employee leave? Why didn’t he have a backup employee trained? Why is it necessary to look outside for a replacement? These and many other questions always remain unanswered by management. In this precarious environment, it’s easy for your prospective telehirer to trip and tumble.

Marilyn Moats Kennedy perfectly described the result in Office Politics:

[T]he troops will be completely demoralized and convinced that if they are smart, they’ll leave. ‘Every man for himself’ will prevail.

The leaving of the best and brightest is the equivalent of a run on a bank. The human working capital of the company is being withdrawn, and what is left may not be enough to sustain the organization.

[Supervisors] will try to control the situation by reassuring the present employees or by moving about in secrecy. The first is a reasonable strategy; the second is ridiculous.

2. Making the right decision.

Making no decision at all is better for an untrained “unhirer” than making the wrong one. Politically, your replacement guarantee is a nightmare, since hiring preferences constantly change. If you’ve ever had to honor one, you understand how tortuous it is for both parties. Even a novice supervisor knows he’s got to be right the first time.

Sonya Hamlin described the typical hirer in How to Talk So People Listen:

The anxiety about our own competence doesn’t ever really leave us. Whenever you, the teller, present a challenge to move into the ‘Learn this because there will be a test’ mode, you can call up levels of performance anxiety.

Thus the normal human instinct of self-preservation causes us, the recipients, to put our hands up in front of our faces and say, ‘Whoa!’

3. Avoiding hassles.

Interviewing is only fun when you’ve got nothing else to do. A motivated hirer is a firefighter who has to turn off the hose while the flames are licking his desk. He doesn’t want to be distracted by his hiring problems, but he wants them solved. It may not be logical, but logic is scarce in the hiring process anyway.

Lyn Taetzsch and Eileen Benson noted the effect in Taking Charge On The Job Techniques for Assertive Management:

You can’t communicate what you want if your goals and standards are vague or changeable… If you accept a late report without comment in one month and become furious in another, your employees [and management] are likely to end up confused and resentful.

You may not even be aware of your inconsistencies.

Tactic #2: Reposition Yourself

You’re already in a very compromising position when you call. It’s endemic to the, “What have you done for me lately?” nature of non-exclusive, contingency-fee search.

Chapter 10 in The Placement Strategy Handbook is entitled “Educating Employers on Recruiting.” We began by quoting an employer who said: “I have very little respect for agencies because all they really do is take my job order, then send me cadres of ‘perfect’ job applicants hoping I’ll weaken and hire one of them.”

“Agencies” and “applicants.” Do you reposition yourself by being an “executive search consultant” who places “candidates”? No. You’re still in that compromising position — bent over.

Proper positioning doesn’t happen by using canned openers. It happens by believing in the value of search.

Zig Ziglar discussed how belief becomes reality in Secrets of Closing the Sale:

How many times have you seen a new and untrained person come into your organization? He doesn’t know any of the ‘bear trap’ closes, doesn’t really know scientifically, psychologically or technically how to deal with all of the fancy objections, but oh, brother does he ever believe in the product he’s selling!

You’ve gotta believe . . . [H]onesty means we believe so deeply, so completely, so fervently in what we are selling that we can’t understand why other people don’t buy. When our belief is that deep, our prospect picks it up.

You see, selling is a transference of feeling.

It’s not necessary for you to use a script to convey that belief. In fact, you shouldn’t. John Truitt wrote how you will convey honest belief naturally in Telesearch: Direct Dial the Best Job Of Your Life:

You may not realize it, but you will actually have a tremendous advantage over the people on the other end of the line in your ‘telesearch’ conversations. You know what you called for in the first place — they don’t. You know exactly what you will say and where the conversation will be headed — they don’t. You even know what they will probably say, and you already have an answer for it…

If you have only half as much faith in me as I have in you, you will be successful.

When you believe in yourself, you train a telehirer. She trusts you. After all, you know best what you can do. She doesn’t doubt you unless she senses that you doubt yourself.

Here are a few of the classic ways that happens:

Being unprepared: Unless you use something like the profile, you’ll fit this category. You need to apologize when you ask a frantic firefighter the basics.

From then on, you’re crawling around on your carpet.

Being mechanical: The dialogue of a cold call shouldn’t consist of automatically reciting questions from a job order form. Enhancing receptiveness to the recruiter isn’t on any of them.

In Chapter 10 of The Placement Strategy Handbook, we also suggested:

Try to make every job order a special situation. Make every employer think that you’ll be dropping everything to concentrate exclusively on its special need.

Employers become more responsive and cooperative when they think you are focusing all of your effort and attention on their needs rather than just trying to win a sendout contest.

Launa Huffines added in Connecting With All the People in Your Life:

If you speak simply and clearly from your from your own wisdom, instead of speaking about something you’ve read or been told, you will stimulate others to respond from their own wisdom. Ideas will suddenly become clear to you in response to thoughts others express, and you will find yourself saying things you have never thought of before.

Whether your conversation is humorous or serious, simple words are always best. The higher the level of wisdom you reach, the more straightforward your words.

Being disorganized: Do you have a logical list of questions to ask that go deeper and wider than the JO?

If not, use the 49 we covered in Chapter 19 of The Placement Strategy Handbook entitled “Writing The ‘Perfect’ Job Order.”

We separated the questions into those about the employer, department and job. You can download a sample client profile here; just click the image. The first 15 questions are included to give you a sense of what you need to know.

We separated the questions into those about the employer, department and job. You can download a sample client profile here; just click the image. The first 15 questions are included to give you a sense of what you need to know.

The human brain thinks in a logical, orderly sequence. A disorganized recruiter is more than unprofessional — she’s ineffective.

Being tired and uninspired: Both of these things happen constantly because unlike an in-person seller, you’re always “on.” Either you’re calling someone or they’re calling you. Either way is essential to making placements.

Alert, can-do recruiters are the ones hirers use. I discussed how they operate in Surviving Corporate Downsizing:

They have a native’s understanding of the job market and an objective knowledge of employers from the inside out. From candidates, cold calls, job orders, industry directories, annual reports, trade shows, and hundreds of other sources they develop a sixth-sense understanding of the games, the plays, the players, and the scores.

They have to be sharp. There’s only one law: Survival of the fittest.

Being unreal: This happens in a variety of ways. The most common is the recruiter who chuckles when asked how he’ll find candidates. Then there’s the one who says he’ll “steal” someone from their job. How about the one who’s “friends” with all the major players in the industry?

These are absolute turnoffs to a hirer. Hirers are no different from you or me — only more pressured in different directions. They are governed by that indomitable law of human nature: We like people who are like ourselves.

Hirers observe that law. It’s called the “halo effect.” When that hirer identifies with a candidate, he’s hopelessly hired.

When he identifies with you, it’s a happy hiring too.

Hamlin noted:

New ideas [you and your ways] are usually presented just that way — as new. Different. Unlike what’s gone before. Bad news! This doesn’t give the [hirer] any grounding or context or reason to believe he/she can tune in. We all need to feel some ownership of turf before we venture forth into the unknown.

“Turf” in this case means knowing that past information, experience, and one’s background are valuable and useful in a new situation. New data creates major resistance since one doesn’t know how to listen to it, relate to it, or even imagine it.

The safest way to discuss new information is to begin with what is known. To start with the familiar.

What Hiring Managers Think

Are recruiters guilty of conveying disbelief in search? Search Research Institute once asked a few dozen supervisors their cold-call “recruiter reactions.” Here are the adjectives it received:

| Ambiguous | Formal | Secretive |

| Arrogant | Irrelevant | Stuffy |

| Artificial | Nervous | Unfriendly |

| Cold | Patronizing | Unsure |

| Complex | Pompous | Vague |

| Disinterested | Rigid |

Of course, cold calls tend to get cold responses. And asking supervisors their recruiting reactions suggests negative answers are expected. But those reactions are accurate enough — they’re just not always expressed.

These are the tribal tactics to train telehirers. They work.

Tell your friends!