Over the past year, the Department of Labor has taken a newfound interest in the number of Asians working at tech companies in Silicon Valley. New allegations and statistical analysis methods strike at the core of long-standing hiring practices and workforce demographics. First, I’m going to explain a recent settlement in a critical U.S. government lawsuit. Then, I’m going to offer you a fresh look at what it means and provide a few tips to help you play the confounding numbers game perpetuated by the OFCCP.

Palantir Agrees to Pay $1.7 Million to Asian Applicants

On April 25, 2017 the OFCCP released a statement announcing they had entered into a consent decree with Palantir Technologies Inc. to resolve charges of systemic hiring discrimination at the company’s Palo Alto facility. It settles a suit initiated last year, where the OFCCP alleged Palantir Technologies discriminated against Asian applicants in the hiring and selection process for engineering positions.

According to allegations in the original complaint filed by the OFCCP in September 2016, from January 2010 to the present, Palantir violated Executive Order 11246 by discriminating against Asian applicants, particularly during the resume screen and telephone interview phases, and by hiring a majority of applicants from an allegedly discriminatory employee referral system.

Under the terms of the decree, Palantir will pay $1,659,434 in back wages and other monetary relief — including the value of stock options — to the affected class and extend job offers to eight eligible class members. The “affected class members” are “Asian applicants who submitted applications for the QA Engineer, Software Engineer and/or QA Engineer Intern position at any time during the period January 1, 2010 to June 30, 2011, and were not hired by Palantir.”

The statistics listed by the OFCCP are as follows:

| Job Title | Applicants | #Asian | %Asian | Hires | #Asian | %Asian | |

| Front End QA Engineer | 730 | 562 | 77% | 7 | 1 | 14% | |

| Software Engineer | 1,160 | 986 | 85% | 25 | 11 | 44% | |

| QA Engineer Intern | 130 | 95 | 73% | 21 | 4 | 19% |

Did Palantir recruiters manage to secure a pool of 1,160 applicants for software engineer positions in Palo Alto, California, who were all equally qualified for the position and ready to work given any relocation, work authorization, and/or specific experience requirements? Probably not.

The decree does not define the term “applicant,” but it does reference Palantir’s hiring requirements when it comes to the company’s agreement to make job offers to effected class members. It is only here that the OFCCP acknowledges that not all applicants will meet the company’s hiring requirements. Yet, if a disproportionate percentage of Asian applicants do not meet hiring requirements, because of the way the OFCCP calculates data for purposes of discrimination, the innocent culling of unqualified applicants may drastically skew the numbers and look discriminatory.

Is there a problem when it comes to hiring and pay disparity in STEM fields? Absolutely. Check out this unfiltered look at the reactions of some people in the field to the Palantir case in this YCombinator forum. Although many of the comments are clearly discriminatory generalizations that support the concept of an inherent bias against Asian Indian IT workers, valid points are raised about the definition of a qualified applicant and the question mitigating issues that would disqualify what would seem like a disproportionate number of Asians.

In Related News …

Earlier this year, the OFCCP announced it is also suing Oracle for its “systemic practice of favoring Asian workers [specifically identifying preference for Asian Indians this time] in its recruiting and hiring practices for product development and other technical roles, which resulted in hiring discrimination against non-Asian applicants.” The complaint in that case alleged that Oracle hired 82 percent Asians for a specific technical role where 75 percent of the applicants were Asian. It follows with the allegation that Oracle then turned around and discriminated against the Asians they showed preference for in hiring by ultimately paying them less than whites in equivalent roles.

Oracle’s likely response? It hired the most qualified labor it could find at the lowest possible price. Any IT Recruiter who has spent time working in third-party staffing can tell you the result — a high percentage of Asian Indian workers who are paid less than their White counterparts.

You Can’t Beat the OFCCP

The U.S. government relies on Palantir to handle a giant chunk of its big data analytics, yet it apparently decided they weren’t the experts anymore after the company responded to the OFCCP compliance complaint by pointing out that its aggressive method of rooting out discrimination is based on a flawed system of statistical analysis.

This article from 2014 provides a good picture of the frustrations faced by many organizations subject to the jurisdiction of OFCCP after it started using a purely statistical analysis of applicants to weed out “systemic discrimination” — usually where there has not actually been an individual complaint.

The biggest issue in complying with OFCCP regulations is the fact that the anti-discrimination laws it seeks to enforce specifically prevent companies from asking many of the questions they need to ask to comply with all the conflicting employment laws and government contract obligations they are tasked with handling.

The Good Citizen

The biggest dichotomy of all when it comes to government contracts is that federal agencies may only employ United States citizens and nationals (residents of American Samoa and Swains Island) in the competitive service. Although government contractors may sometimes bring in non-citizens to do work, at times, security clearance becomes an issue. Often, government contracts require citizenship; however, private-sector employers are not allowed to discriminate in hiring on the basis of national origin or citizenship if someone is authorized to work in the United States unless it is required by federal/state contract or law.

So the government will tell you that you have to discriminate to perform the work it has contracted for you to do, but you can’t discriminate in your overall hiring practices. This is where it gets very tricky for companies like Palantir, who only started garnering private sector contracts a few years ago and even in 2016, 30-50 percent of its business was tied to the public sector. This is the other major factor that further explains the reason why Palantir may have gravitated toward a U.S. based workforce, and specifically U.S. Citizens, thereby skewing their demographics ad compared to other tech start-ups that rely heavily on foreign nationals. As explained further below, there is a direct correlation between the number of foreign nationals a company hires and the overall demographic of its workforce.

However, since there are a few agencies that don’t require citizenship, and not all the positions filled by the company would for sure be performing work that required citizenship, they likely couldn’t make it a basic job requirement.

There’s a Giant Indian Elephant in the Room and He Needs a Visa

There’s a giant piece to the puzzle that few sources have brought up — and it’s an issue perpetuated by another government employment program that requires interdepartmental collaboration — the notorious H1-B visa.

Around the same time covered by the Palantir decree and for an extensive period afterwards I was running an IT staffing company. I have personal experience watching the influx of IT professionals from India who applied to any open position that might offer H1-B visa sponsorship and ultimately a path to a green card. This reality will skew the numbers for any technology company.

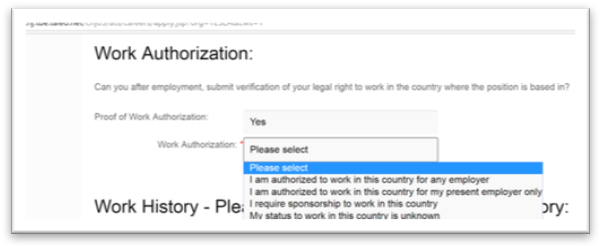

While you can ask about work authorization on employment applications … very carefully … it is unclear how the OFCCP factors this in when it comes to the overall “applicant pool” used for determining if there is evidence of systemic discrimination. However, if the inquiry is not included on the initial application (Palantir does not ask about an applicant’s work authorization), collecting the data at a later stage is guaranteed to be a compliance nightmare and factored out when the OFCCP shows up for an audit.

Example of an application for Tesla that properly asks about Work Authorization.

While it is legal to turn down all applicants who require certain types of employer based sponsorship to work in the United States, which tends to drastically change the demographics of the applicant pool for a position such as a Software Engineer, when an employer does offer visa sponsorship for a position, current authorization to work in the United States without sponsorship becomes a “preferred qualification” instead of requirement for consideration.

Maybe the OFCCP should focus some attention on tackling the systemic discrimination in the U.S. H1-B Visa lottery itself. After all, in 2016 82 percent of all new H1-B visas were issued to foreign nationals from India and China.

Surprisingly, the OFCCP seems to expect companies to hire based on the same flawed system that causes so many H1-B visas to be issued to Asians. Foreign nationals seeking sponsorship tend to flood a company’s ATS the same way Indian outsourcing companies like Infosys and Tata Consulting flood the U.S. government with applications for H1-B visas. Compare the percentage of Asian applicants for IT jobs in the Bay Area at Palantir and Oracle to U.S. census records from 2010. Including the vast number of temporary foreign workers in Silicon Valley, Asians made up about 50 percent of the Bay Area population demographic in tech occupations.

You Want More Asians? We’ll Get Them! … From Asia

Looking further into the Department of Labor’s archives, Palantir had a total of five applications for H1-B visas and one application for a Green Card Certified from 2010-2011 at its Palo Alto location. Conversely, in 2013, at its Redwood Shores location alone, Oracle had a total of 371 applications for H1-b visas and 115 applications for Green Cards Certified. Of the Green Card applications certified, all but 64 were for foreign nationals from India. The data only indicates the number of applications filed by each company. It does not mean that the company actually obtained the visa and hired the workers. H1-B data also includes both new H1-B visa applications, transfers and renewals.

Granted, the number of employees at Oracle is and was exponentially higher than Palantir, and as the organization grew in size, so did its number of applications. The fact that Palantir only recently started sponsoring H1-B visas and green cards on a regular basis may account for one piece of the puzzle when it comes to the demographic of its workforce. The other factor that the OFCCP does not figure in to its audits are the demographics of a company’s subcontracted workforce. The staffing companies that provide contractors to companies like Oracle and Google likely have a completely provide a completely different demographic ratio than that of the workforce internally recruited for employment.

As the new administration attacks the current H1-B visa system, everything is likely to turn on its head. In fact, one major IT outsourcing company just blew the whistle on the fact that the net cost of bringing talent in under the program has now made the long-standing marketplace of bringing in inexpensive IT workers from Asia unprofitable. If salary requirements for these workers are raised as expected, the OFCCP is likely to see a massive statistical shift in Asian hiring.

Striving for a Diverse “Workforce”

Despite the fact that any HR professional will tell you it isn’t supposed to work this way, the shared services model used by many tech companies often means that internal workforce analytics systems don’t provide a complete picture of all “Software Engineers” working for the company. Whether or not it is being done in a compliant way, tech companies often have workers performing the exact same job function, where some are employees and others are jointly employed by a staffing company or as part of an RFP with a consulting company. When evaluating compensation data and other discriminatory practices for a company’s employees, other non-employee workers are not included. In fact, most of the time the client corporation can’t provide the information because they have no idea how much John Smith is being paid. They only know how much they are paying ABC Consulting.

Palantir’s argument that the OFCCP uses flawed statistical systems is completely valid. Moreover, any results are based on impossibly flawed employment data, perpetuated by most companies’ efforts to obtain the talent and workforce they want while still attempting to comply with all the other government regulations they are facing — agencies where noncompliance carries a much larger risk and much bigger fines.

Making Up the Numbers

Is there actually a way to win this numbers game, or should government contractors just set aside a percentage of revenue to settle with the OFCCP when it eventually decides it’s their turn to pay the government watchdog tax? Palantir seems to have decided to pay the piper. After all, while $1.7 million dollars may seem like a big number, it is less than 0.5 percentof the $420 million or so the U.S. Government has paid the company for contract work since 2008.

All valid defenses aside, Palantir probably could have done a much better job of ensuring its hiring practices met the OFCCP standard. However, back in 2010, it was still a relatively small startup no one had ever heard of. It wasn’t until 2010-2012 that the company had to go on a massive hiring spree to cover a giant spike in business. Government contracts alone jumped 400 percent in 2011. Trying to keep up with OFCCP recordkeeping demands as a small, rapidly growing business is next to impossible no matter who your VC backers are.

The reality is, it’s difficult to balance the desire to ensure a welcoming candidate experience and a simple job application process while also ensuring to weed out unqualified applicants at the first step. In the case of Palantir, “Asian applicants were routinely eliminated during the resume screen and telephone interview phases despite being as qualified as white applicants.”

This probably happened because, even six years later, Palantir doesn’t ask for a whole lot of information on its applications. Without qualifying questions at the time of application, much more subjective steps performed by recruiters later in the process are the first opportunity to eliminate candidates. The OFCCP may consider things like the need for a visa — a genuine issue when they show up for an audit, but it is a lot less likely if it isn’t determined on the initial application. The best bet is to follow the old standard: Document, document, document.

- Strictly define when a candidate is considered a “qualified applicant”

- Include disqualifying questions on the corporate application portal

- Specifically ask and track work authorization and if current or future visa sponsorship is required for a candidate to work in the United States

- Track the entire screening process and include notes regarding disqualification at each stage of the process

- Make sure all hires are actually qualified applicants

Then, if the OFCCP comes knocking, throw your data at them and hope for the best. Half of the complaints filed are based on continued requests for information that the company is unable or unwilling to provide. To all the federal contractors out there, good luck! We are likely to see a dramatic shift in enforcement priorities and some brand new executive orders the OFCCP will be tasked with enforcing. For the first time ever, “post and pray” might actually be sage advice.

This article and any links provided are for general informational purposes only and should not be construed as professional or legal advice.

image from bigstock